Cloud Engine energy center

Formerly home to the state-owned Yuzhou Ceramic Factory and the Ceramic Machinery Plant, Taoxichuan has transformed into a nationally recognized hub of cultural innovation. Today, it stands as a National Cultural Industry Demonstration Park, a National Innovation & Entrepreneurship Demonstration Base, a National Night-time Cultural and Tourism Consumption Cluster, and a designated National Intangible Cultural Heritage Tourism District.

It has become a vibrant stage for countless “Jing-drifting” artists and creators who have made Jingdezhen their home.

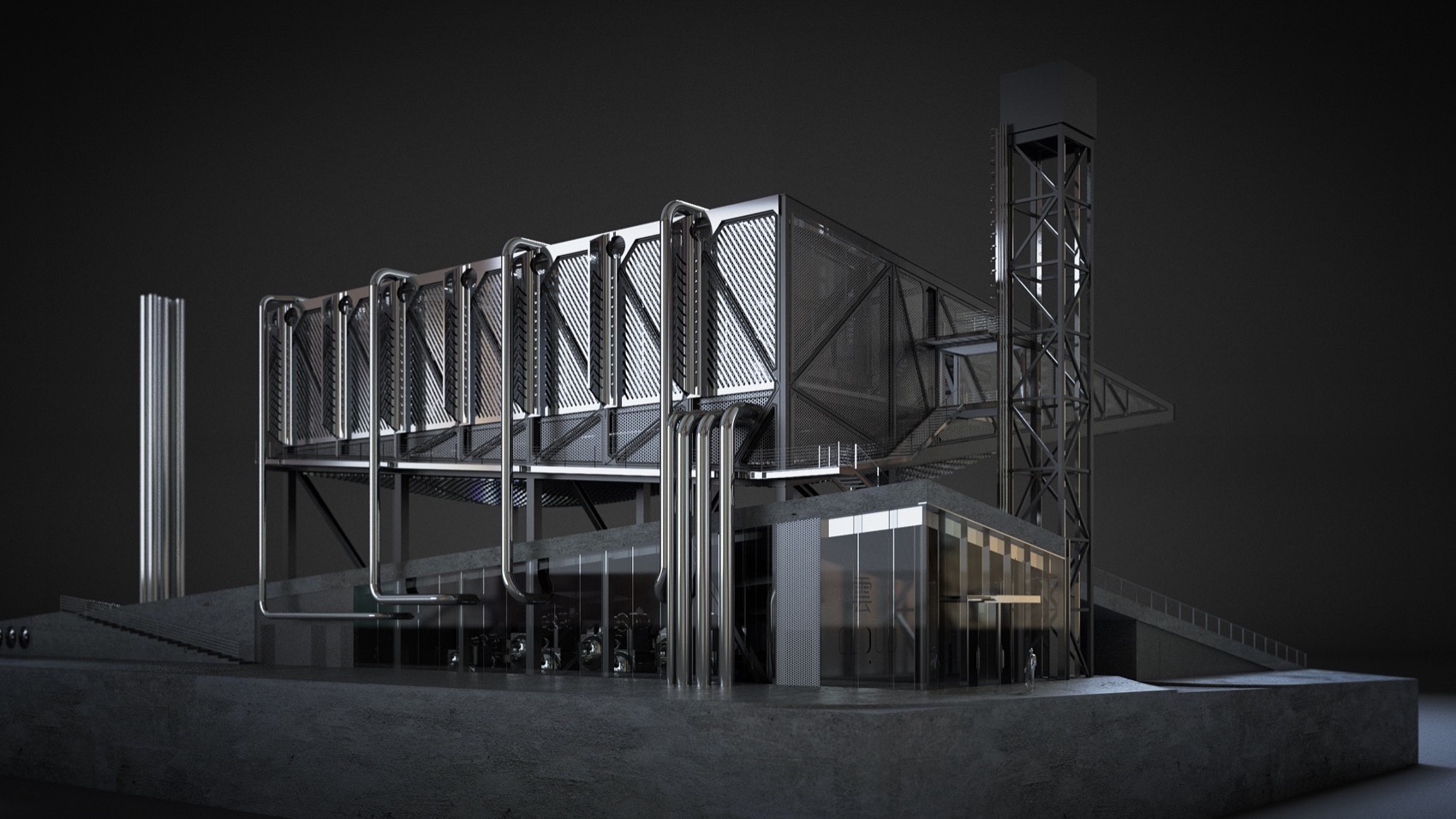

An energy station—commonly referred to as an equipment room—is typically not open to the public. It houses essential infrastructure such as fire-fighting water tanks, pump rooms, boiler rooms, cooling units, substations, and control centers. These functions are usually packed into a large sealed box, topped with oversized cooling towers and wrapped with layers of louvers.

Architects, with their trained sensibilities, can devise countless façade strategies to beautify this box. But the real question is: can we satisfy all the operational requirements of an energy center while maximizing the openness of the park?

Our approach divides the building into two parts:

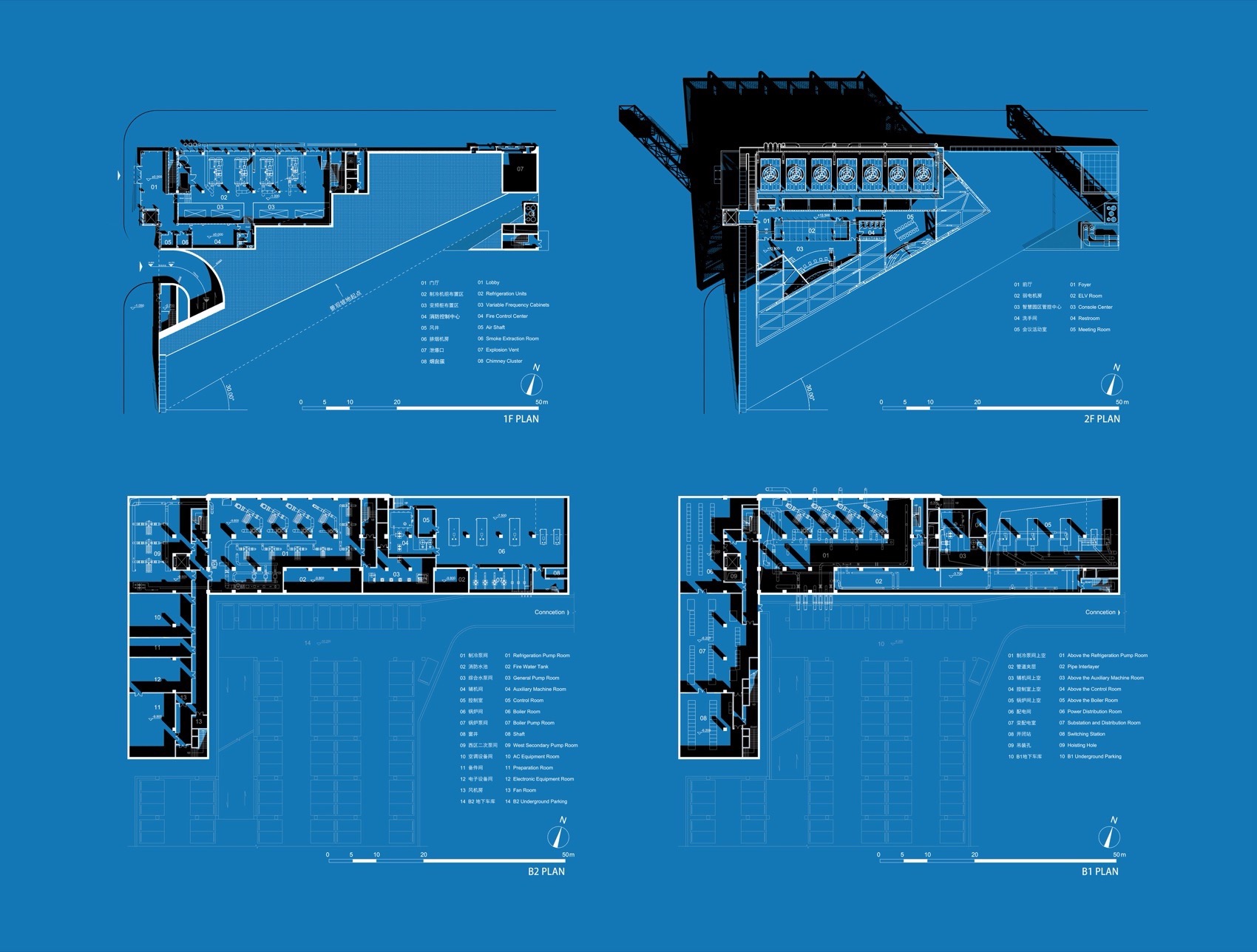

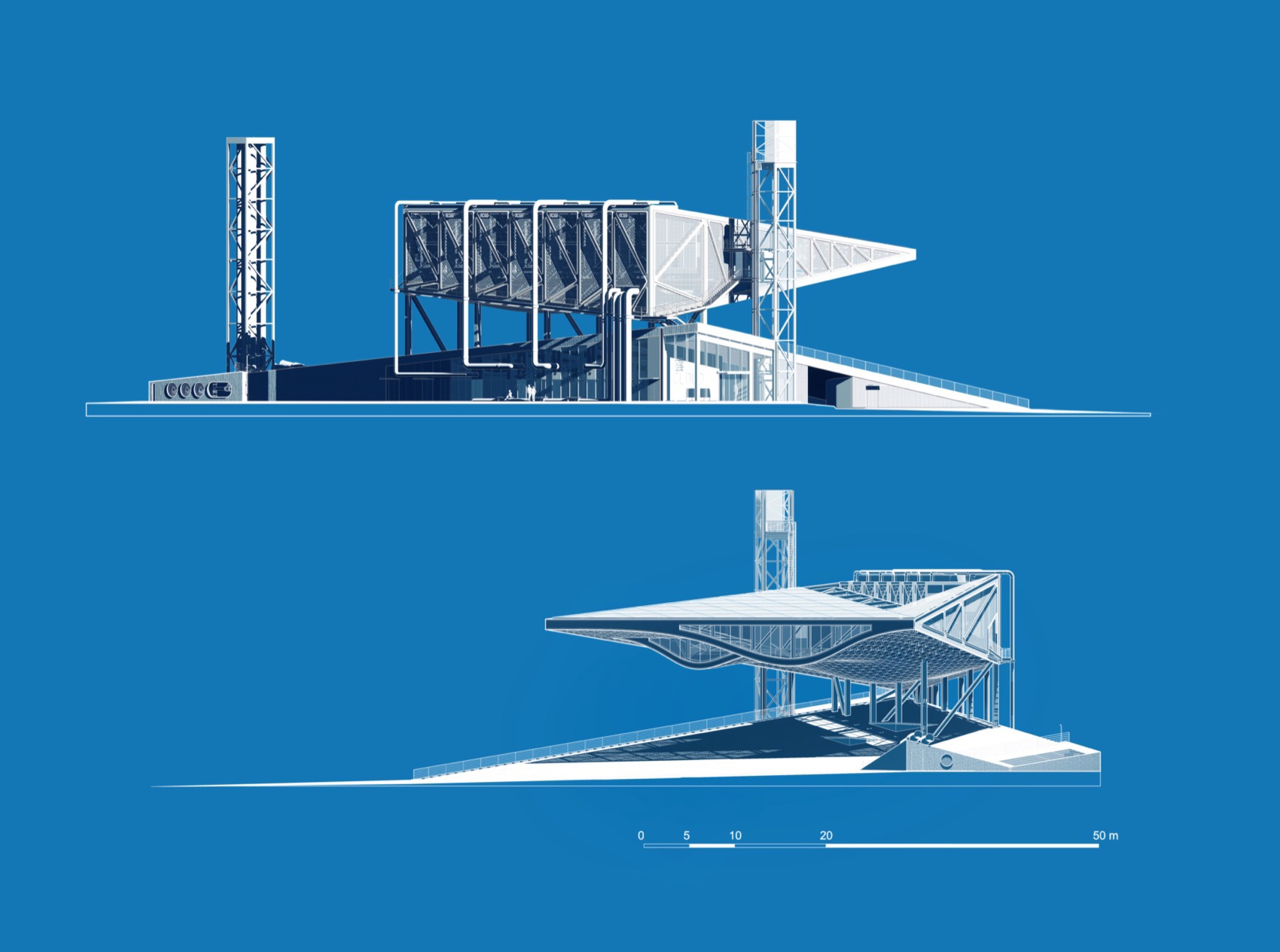

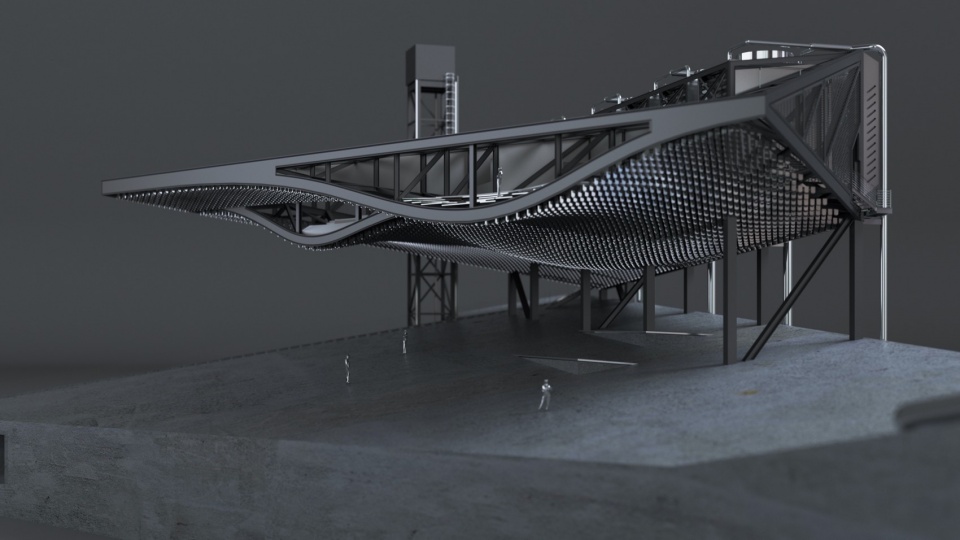

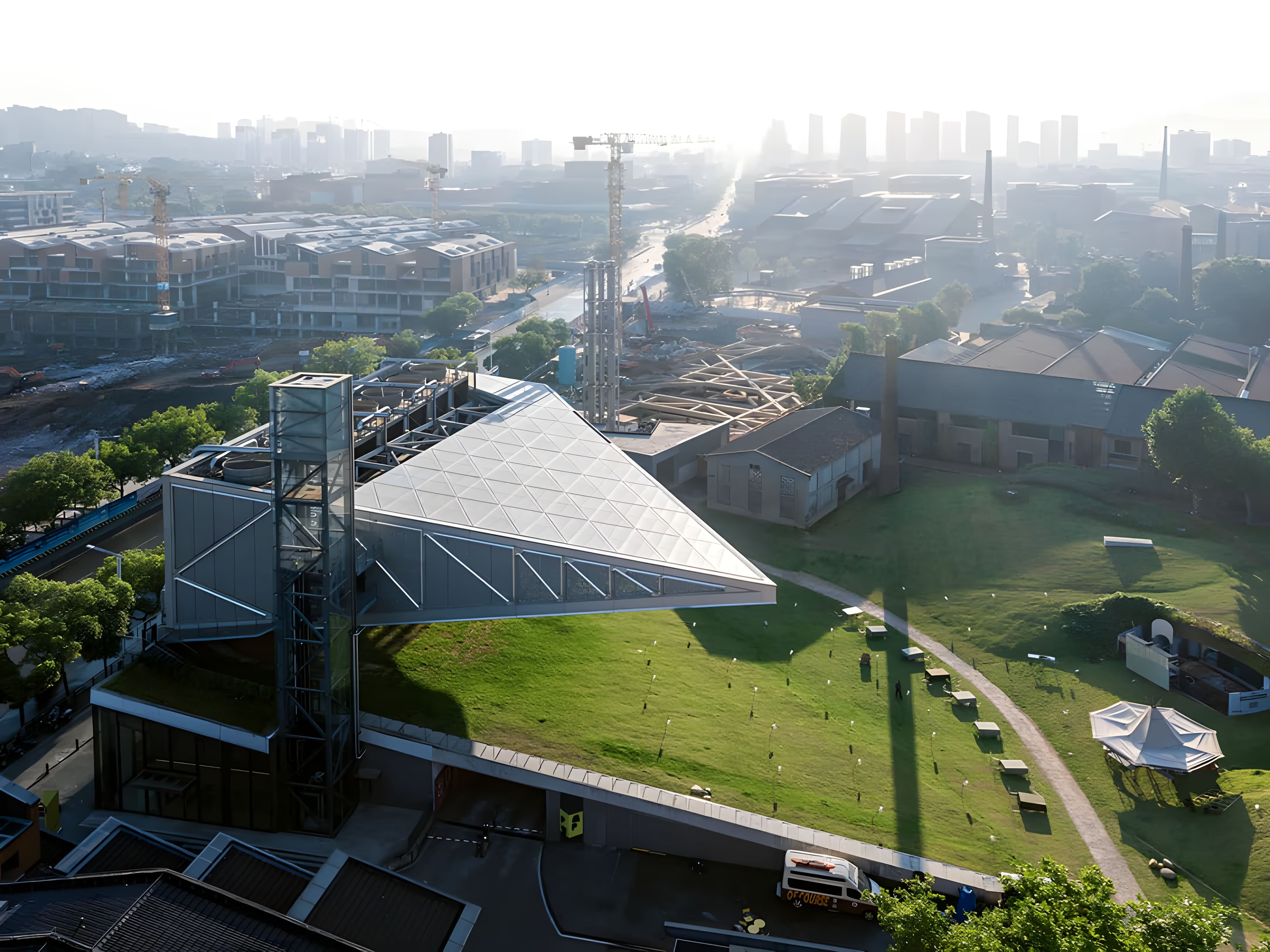

The cooling units, power distribution rooms, boiler rooms, and fire-fighting water tanks are placed underground and merged with the landscape, forming a gentle grass slope—like lifting a corner of the earth itself. Above, the cooling towers and control center float in the air. Their volumes are arranged according to spatial needs, forming a clean, wedge-shaped composition.

Although the facility itself is not open to the public, splitting the building into two volumes allows the ground it occupies to be returned to the park. The overall public green space remains undiminished.

In the height of summer, the vast structure above becomes a generous “shaded canopy,” creating a comfortable, breezy grey zone beneath it—an ideal place for rest and gathering. It also becomes a natural viewing platform for various activities taking place on the lawn.

The north side of the energy center, facing the street, is sharp and mechanical, with exposed equipment and piping giving it the look of a giant machine.On the park side, however, the building becomes lighter and softer. The suspended volume forms two curved “eyes” — the control room and the meeting room — created within the space of the structural trusses.

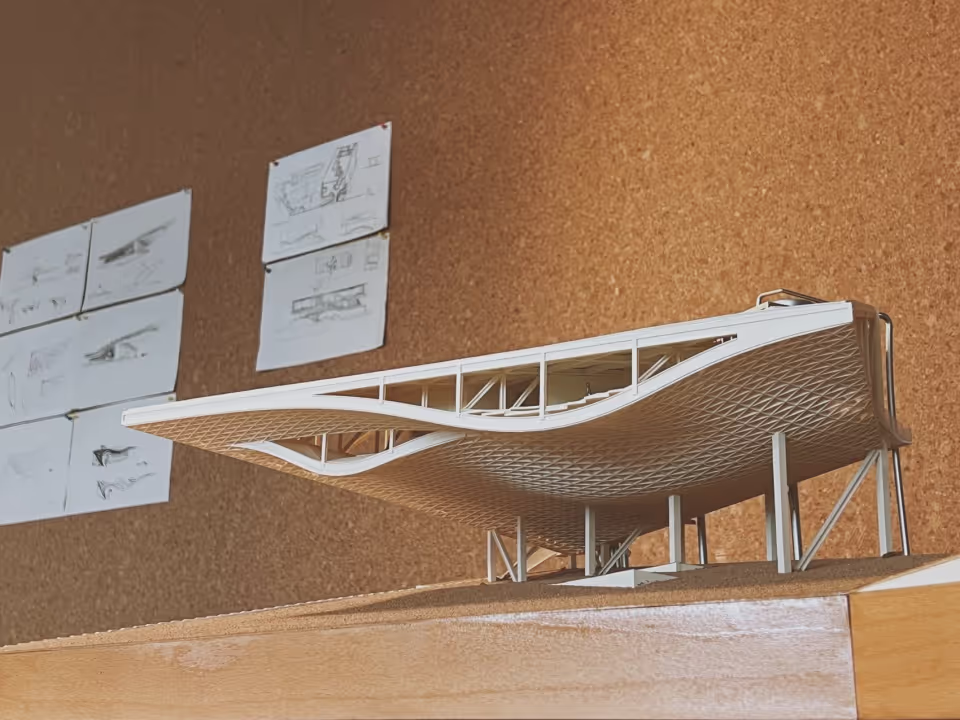

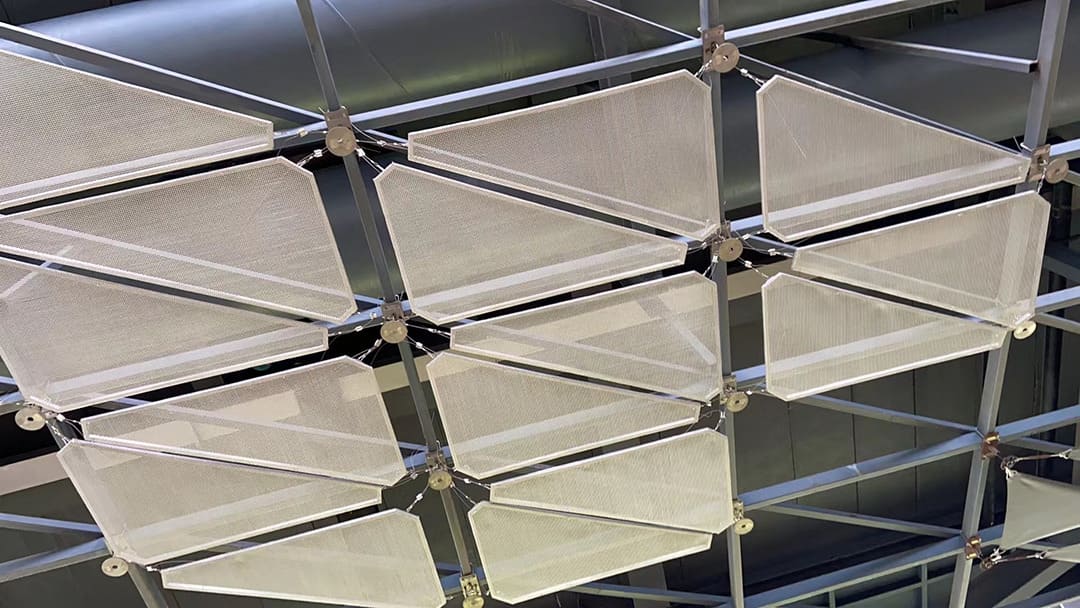

We imagined a layer of wind–responsive shingles suspended beneath the floating volume, moving like wind chimes. As the surface ripples with the breeze, it becomes an art installation within the public landscape — a mechanical cloud hovering above the grass slope.This is how the “Cloud Engine” got its name.

In an energy center, the equipment always comes first. Our calculations determined the cooling load to require three 2200RT and one 1100RT variable-speed centrifugal chillers with seven large cooling towers, while heating is supplied by three 5.6MW gas hot-water boilers and domestic hot water by two 1.4MW gas boilers. These technical specifications form the fixed constants that shape the spatial design.

To accommodate this array of equipment, we tailored the structural grid, coordinating column spans and routing paths to ensure that every space met the technical and mechanical requirements. This demanded a high level of integration between architecture, structure, and MEP systems—made possible only through close collaboration and technical support from the China Zhongyuan team. We developed parametric models to visualize, in real time, how adjustments in any discipline would impact the whole. Beyond digital simulations, we even conducted physical wind-tunnel tests to verify performance.

.gif)

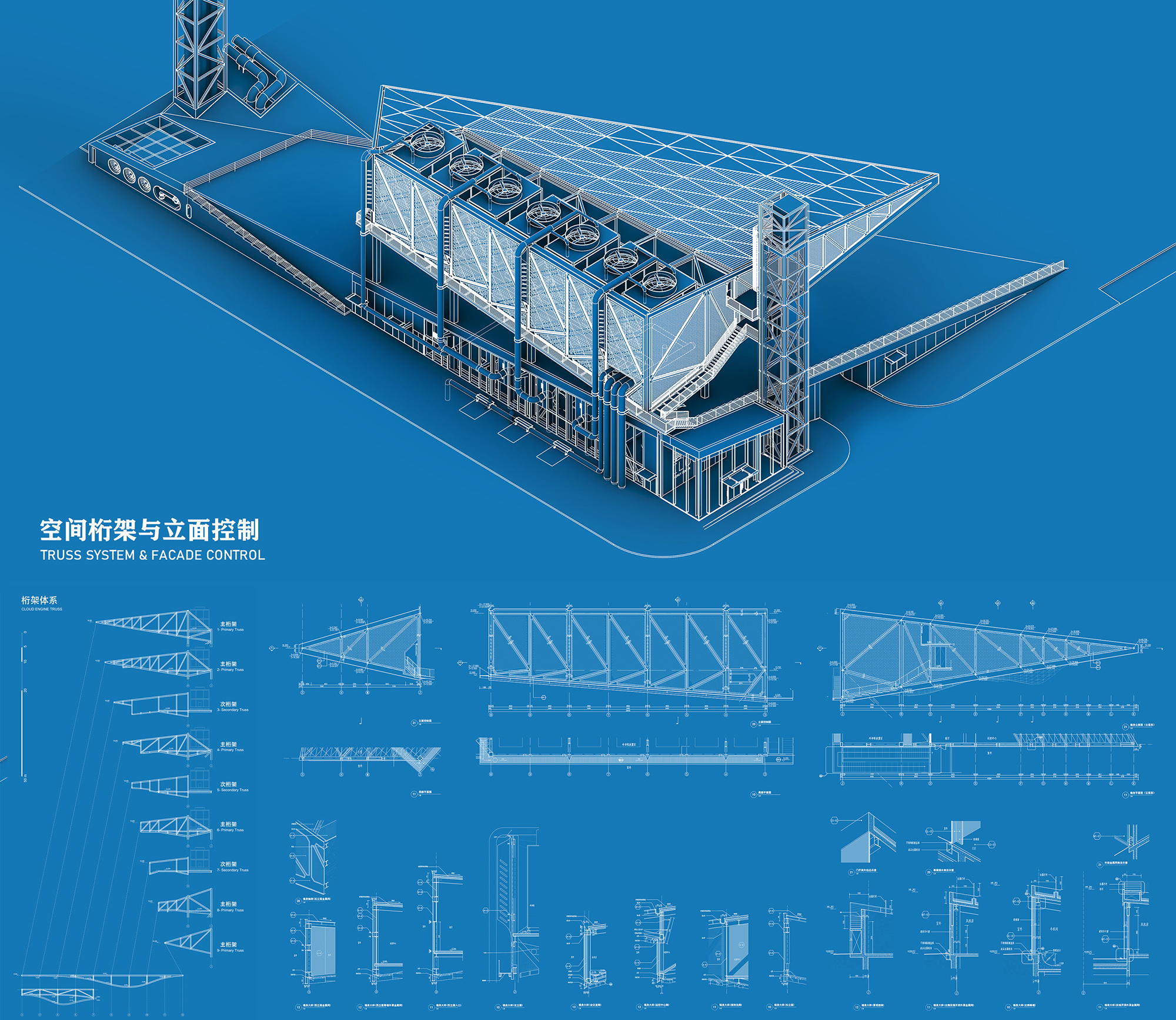

The structure is directly expressed on the façade.

In our view, the technical logic of equipment is a kind of beauty in itself. Yet in traditional architectural practice, this beauty is often either concealed—hidden behind shafts, ceilings, and louver screens—or reduced to a superficial “industrial style” imitated in interior decoration.

In the design of the Cloud Engine, we chose to reveal this beauty honestly and integrate it seamlessly into the architecture, giving the building a coherent mechanical character. On the façade, we directly label functional elements in both Chinese and English—marking “Cold” on the chilled-water pipes or engraving “Access” along the maintenance routes—turning the building’s details into something akin to an operational manual.

Physical Mock-ups and Illumination Tests for the Hanging Shingles

Design Drawings